By Rodrigue Fenelon Massala, senior reporter, special envoy to Addis Ababa

The Ethiopian state is gradually withdrawing from certain sectors, opening controlled breaches, inviting private, domestic, and foreign capital to enter the game. In the streets of Addis Ababa, this fresh wind of renewal whips the face of the visitor.

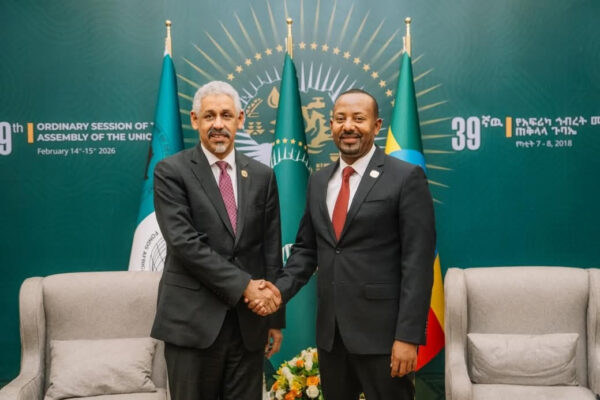

Ethiopia continues its shift from a dirigiste economy to a liberal economy initiated in 2018 with the accession to power of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, the chief reformer. In ministries, there is now talk of “competitiveness,” “sovereign rating,” and “project bankability.” Words that, just ten years ago, would have seemed incongruous. Behind the official narrative of a “national renewal,” there is actually a methodical recomposition of a long-standing statist model, now subject to market disciplines, investor expectations, and geopolitical constraints. The ambition is clear: to shift from an administered economy inherited from previous decades to a regulated, open, and competitive capitalism. This gradual but resolute transition aims to stimulate private investment, diversify exports, and strengthen the state’s budgetary capacity.

From a developmental state to a structured market

For nearly two decades, under Meles Zenawi, Ethiopia favored a model of a “developmental state,” highly centralized, based on large public works, state-owned enterprises, and control of strategic sectors. This scheme, effective in supporting rapid growth in the 2000s, eventually showed its limitations: low productivity, dependence on external debt, underdevelopment of the private sector. Abiy Ahmed’s team has undertaken to correct its rigidities. Since 2024, the authorities have initiated a series of major structural reforms: gradual liberalization of the birr, partial opening of the banking sector, deregulation of telecommunications, and systematic encouragement of public-private partnerships. This is not just administrative modernization, but an attempt at strategic repositioning in the global economy.

Growth under high tension

According to official projections released in early 2026, the Ethiopian economy could achieve growth close to 10% in the current fiscal year. A remarkable performance for a country just emerging from a major internal conflict. The Tigray War (2020–2022) is estimated to have cost the national economy over $28 billion in infrastructure destruction, lost productivity, and disruption of logistics chains. Few African economies have shown such a rapid rebound after a shock of this magnitude.

This recovery is largely based on the revival of exports. In 2025, coffee revenues increased by over 80%, reaching around $2.6 billion. Gold, long marginal, now accounts for over 40% of export revenues. In addition, there are horticultural products, leather, and gradually, some manufacturing productions. Ethiopia is thus attempting to move away from its historical dependence on a few raw materials.

Monetary reforms and controlled opening

The liberalization of the exchange rate, initiated in 2024, is one of the most sensitive turning points. The birr, long overvalued, penalized exporters and favored distortions. Its flexibilization, though painful in the short term, helped improve external competitiveness and attract more foreign currencies. At the same time, the opening of telecommunications and financial services to international competition marks a symbolic rupture. The arrival of foreign private actors, especially from the Gulf and Asia, deeply alters the balances of a long-locked sector. This choice reflects a conviction: economic sovereignty no longer lies in public monopoly but in the ability to effectively regulate open markets.

Economic diplomacy and diversification of alliances

Excluded since 2022 from the U.S. commercial program African Growth and Opportunity Act, Ethiopia had to rethink its external outlets. This constraint accelerated its pivot towards China, the Gulf countries, and certain Asian partners. Beijing remains a major creditor and investor, especially in infrastructure and industry. Middle Eastern sovereign funds target agro-industry, energy, and logistics. Addis Ababa thus cultivates a pragmatic, multipolar, sometimes opportunistic, but rarely naive economic diplomacy. At the same time, the country is negotiating a delicate restructuring of its external debt, estimated at over $30 billion, in a less forgiving international context than before.

Addis Ababa, a laboratory for modernization

In Addis Ababa, the transformation is visible. New business districts, modernized railway infrastructure, logistics hubs, peripheral industrial zones: the capital presents itself as a showcase of a transitioning state. However, this modernization remains unevenly distributed. Disparities between dynamic urban areas and fragile rural regions remain significant. The growth, as spectacular as it may be, has not fully corrected social imbalances yet.

A success still conditional

On a macroeconomic level, the signals are encouraging: improved exports, increased confidence from donors, sectoral diversification, and the rise of light industry. Ethiopia is gradually establishing itself as an emerging industrial hub in East Africa.

However, this trajectory remains under strict conditions.

Political stability remains fragile. Intercommunal tensions, peripheral security challenges, and unfinished institutional balances pose structural risks. Financial credibility will depend on the government’s ability to control debt and strengthen budgetary governance.

Furthermore, investor confidence rests on a central factor: the predictability of the rules of the game. Without a robust legal framework, independent economic justice, and increased transparency, liberalization could lose its substance.

The speed of the rebound

Today, Ethiopia is walking a tightrope. Between reformist voluntarism and persistent vulnerabilities, it seeks to establish itself as a credible, disciplined, and attractive regional economic power. Abiy Ahmed’s project is neither a mere political facade nor a conjunctural improvisation. It is a deliberate attempt to refound the national model, inspired as much by Asian experiences as by African constraints.

The question remains whether this demographic giant of over 120 million inhabitants will be able to transform this momentum into lasting prosperity. The answer will not only depend on growth figures but also on the country’s ability to reconcile openness, cohesion, and rigor.

This is perhaps the true test of maturity for contemporary Ethiopia.