From Pretoria to Libreville, AfCFTA hindered by the awakening of nationalisms

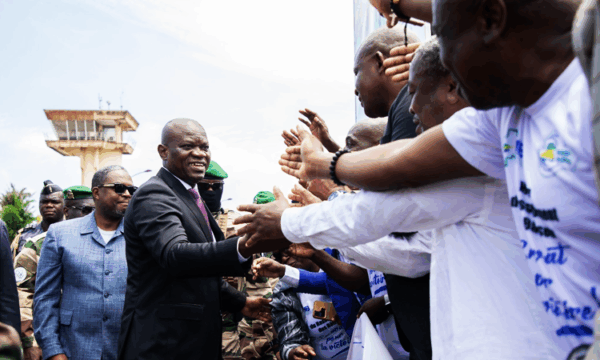

The government of President Brice Clotaire Oligui Nguema has announced the ban for foreigners – mainly Cameroonians, Nigerians, Malians, and other West African nationals – from operating small businesses. Presented as a measure to protect national operators, this decision is part of a strategy of “Gabonization” of urban economic circuits. Behind this, a political calculation: to attract an urban electorate often hostile to foreign competition in retail, a sector where the average profit margin can reach 20% but where rents and charges weigh heavily on margins.

After the announcement at the Council of Ministers on Tuesday, August 12, the Gabonese government decided to ban expatriates from practicing certain small trades. This is to combat unemployment and gradually take control of the country’s small economy. Foreigners living in Gabon are now prohibited from engaging in local commerce, sending and repairing phones and small devices, street hairdressing and beauty care. The same goes for artisanal gold mining, crop purchasing, operation of small workshops or gaming machines.

According to the Gabonese press, current tensions stem from the allocation of spaces in a recently inaugurated market in Lambaréné to foreign female traders, mostly from West Africa, to the detriment of many local vendors. This situation has fueled accusations of “social injustice” and reignited identity tensions.

Gabonese people are divided on the effectiveness of the measure. This decision illustrates a broader trend on the continent, where the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which came into effect in 2021 and is supposed to create a single market of 1.3 billion people with a combined GDP of over $3 trillion, is facing nationalist reflexes. Gabon is just one of many examples. In South Africa, the Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) continues to play a role in economic redistribution, but in a context of mass unemployment (over 32%), the political discourse becomes more exclusive. Figures like Herman Mashaba, former mayor of Johannesburg (2016-2019), known for his liberal economic views and strong stance on immigration, advocate for the expulsion of Mozambican, Zimbabwean, or Nigerian traders, while xenophobic riots in 2019 and 2021 resulted in 62 and 354 deaths respectively.

In the Maghreb, Tunisia has tightened its administrative restrictions following statements by Kaïs Saïed in 2023 about a supposed “demographic change plan” linked to sub-Saharan immigration. In Algeria, cyclical expulsions of Malian and Nigerian workers in the South officially aim at employment regulation but affect key sectors like construction and agriculture. In Tanzania, the policy inherited from John Magufuli still imposes strict quotas for foreign labor and a minimum local capital of 51% in certain sectors. These rules, rigorously applied, directly impact Kenyan, Ugandan, and Congolese entrepreneurs, even as bilateral trade with Kenya exceeded $900 million in 2021.

In Nigeria, periodic bans on rice, textile, or cement imports also affect ECOWAS neighbors, while in Côte d’Ivoire, the discourse on “economic Ivoirity” resurfaces during social tensions, often around electoral deadlines. As a result, intra-African trade still stagnates at 15% of the continent’s total trade, far from the 65% observed within the European Union. Between discriminatory regulations, arbitrary quotas, and selective customs delays, “invisible barriers” weaken economic integration and risk reducing the AfCFTA to a legal text devoid of real impact.