Peter Doyle, American Economist, ex IMF Senior Staff

When in Fall 2024, Ndongo Samba Sylla and I flagged the absurdity—given the longstanding CFA Franc-Euro peg—of IMF projected 12-month inflation in Senegal of -13 percent for end-2025 and +42 percent for end-2026, we noted that the IMF was clearly not paying attention to the numbers, not even its own. What else, we asked, would emerge?

Little did we know.

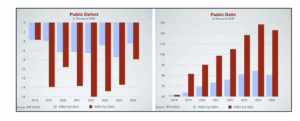

After a change in government in April 2024, forensic investigations recently confirmed that government borrowing from 2019 during multiple IMF programs exceeded levels the IMF had reported, including to the Senegalese public, by over 40 percent of GDP (See Charts). That will burden Senegal for generations.

Senegal: Fiscal Position, by WEO Vintage—2018-2025

That long sandstorm of credit—mainly locally sourced, undetected by IMF staff, and alongside major hydrocarbon finds—followed a similar episode in mid-IMF program in Mozambique in 2016 and an early written warning in 2018 from the opposition (now Prime Minister) of the data deception. But to no avail.

At IMF bidding to secure market access in haste, Senegal’s Parliament recently committed to recognize those debts, as part of an omnibus fiscal bill and so without specific debate. Furthermore, no officials implicated, most still in post covering their tracks, have been penalized. Ex-President Sall, who orchestrated the catastrophe, remains welcome in the highest international diplomatic circles. And no one at the IMF has been disciplined; they simply hiked their medium-term primary balance target by 2 percentage points of GDP and hey presto.

This state of affairs occasions the worst form of moral hazard. Lenders, IMF officials, politicians and technocrats in Senegal and far beyond will conclude that were they to do it again, they would all get away with it, again. And IMF praise for this government’s transparency as bulwark against such smacks of the same earnest naiveté that facilitated the disaster in the first place.

The precedent thus set leaves Senegal’s fiscal institutions now both exorbitantly over-indebted and highly vulnerable to further such assault, all at the expense of some of the earth’s poorest.

This cannot stand.

Key is to stop the haste, root of the entire debacle—as to please bosses, the IMF staff brisk ethos evidently degenerated into taking leave of essential data consistency checks, due diligence, and basic street smarts.

Instead, while continuing full-faith servicing of all other public debts, Senegal should “ring-fence” the stock of unreported debt and stop servicing it pending a full examination. In particular, creditors which broke laws should have those credits written off and lawbreaking officials should be prosecuted. And a rigorous study of where the money went—public/private consumption, investment, and/or capital outflows—should be conducted as that may radically transform the back data, including the level of GDP, and thus understanding of Senegal’s macroeconomy. Absent that, no coherent strategy to address public debt now can be designed.

The only pre-commitment regarding resolution of the unreported debts needed now is that if some is written off that hits to local creditors will be calibrated to keep them above their regulatory capital requirements. That backstops domestic financial stability meanwhile.

That package will chill potential creditors. But far from being a bug, that is a feature: thus stung, their long days of treating the frailties of fiscal reporting with indifference will end.

On the external side, global “ex ante transparency” is also needed to pre-empt recurrence of debt surprises: namely amendments mainly to US and UK sovereign insolvency laws so those courts would not recognize new loans under their jurisdiction anywhere, bar stand-alone IMF Stand-By-Arrangements, unless full documentation was submitted to local Parliaments at least 30 days before signature.

Far from impeding an early IMF program for Senegal, all this is how to make a holding program—while macro data are corrected, presaging a medium-term debt strategy including on foreign currency debt—coherent.

And accountability?

The monstrosity of ex-President Sall parading internationally as eminence grise after presiding over this disaster must stop; he should be a pariah.

Similarly, IMF staff are formally required to vouch for program data, not to hide behind others’ assurances, so IMF labelling of it all as “misreporting” is dissemblance. Instead, the African and Fiscal Affairs Department Directors, responsible for their staff’s quality, apparently never saw wrong in multiple programs despite absurd inflation projections and a colossal fiscal blowout, now capped by a plan which compounds all the errors, designed on uncorrected and so evidently untenable macro data. Accordingly, and to underscore that, no matter what, missing 40 percent of GDP is unacceptable, the Managing Director should dismiss both Directors.

If not, she should be dismissed for tolerating if not driving such a catastrophic failure in IMF staff work.

So, stop the rush: a holding IMF program for Senegal—with ring-fencing, full accountability, and ex ante transparency—is now essential to rescue fiscal institutions there, and, by example, worldwide.