The question of energy subsidies, a recurring issue in African public finances, is making a loud comeback. Originally designed to make gasoline, electricity, or gas affordable, these aids have become an unsustainable burden, draining national budgets and leaving no room to invest in education, health, or infrastructure. Should they be maintained as a safety net, reformed to target them more precisely, or abolished at the risk of fueling unrest?

The positions are clear-cut. Supporters of removal denounce a windfall that mainly benefits the middle and upper classes, far from the vulnerable households it claims to protect. Defenders, on the other hand, argue that in fragile societies, affordable energy is not a luxury but a condition for political stability. The pressures from international donors, led by the IMF, add an additional weight: since the structural adjustment plans of the 1980s, the institution has been urging African states to ease off the subsidy accelerator. Not without consequences: in 2019, the decision to abruptly reduce fuel subsidies in Sudan precipitated riots that toppled Omar al-Bashir’s regime; in 2023, in Nigeria, President Bola Tinubu’s decision to remove subsidies almost cost him his mandate as the streets erupted in protest over the tripling of gasoline prices in a single day.

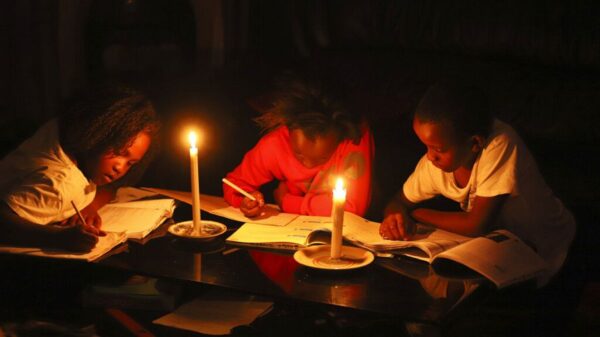

To shed light on this dilemma, two authoritative voices share their perspectives. Dr. Abdourrahmane Ba, a statistician engineer, Ph.D. in management, expert in international development, and author of “Choices and Evaluation of Public Policies in Africa” (L’Harmattan, 2024), puts into perspective the budgetary sustainability of these subsidies and their perverse effects. It is he who, in a striking formula, describes public electricity companies as “giant babies,” maintained at great expense by the State and unable to grow towards industrial maturity. Alongside him, Mbaye Hadji, a pioneer in renewable energies, specialist in energy efficiency and sustainable development, with over three decades of experience in the public and private spheres, winner of the Francophone MILA Prize for his essay “Climate Change: a Heavy Threat to Africa,” argues for an approach more resolutely focused on energy transition. According to him, solar energy, despite its industrial limitations, remains a suitable solution for domestic electricity and vulnerable households, as long as it is supported by targeted support mechanisms.

But the debate is not limited to a duel of experts. Rivo Ratsimandresy, CEO of the Rencontre des Entrepreneurs (RDE), introduces an essential nuance: according to him, energy falls under the sovereign missions of the State. Subsidies, as such, can be maintained in principle. And if reform is necessary, it should be done “from the top” – in other words, by first cutting back on the privileges of the wealthy classes and captive clienteles of public rent, before considering exposing the most vulnerable to market uncertainties.

Adama Wade, publisher of Financial Afrik, broadens the focus: beyond public electricity companies, he points the finger at African refining companies, also perpetually in deficit and reliant on budgetary support. How can it be explained, he asks, that a continent discussing a single currency has not yet considered the idea of “unique refineries”? Combining capacities, pooling investments, and capturing economies of scale would drastically reduce dependence on imports and make the energy equation more sustainable.

At the final whistle of this strategic debate, presenter Dominique Mabika does not take sides. In an elegant turn, she sends the protagonists back to the readers, reminding that the final word belongs not to experts or policymakers, but to the court of public opinion. It is up to each individual to become a peacemaker in this budgetary dispute where nothing less than the energy destiny of the continent is at stake.