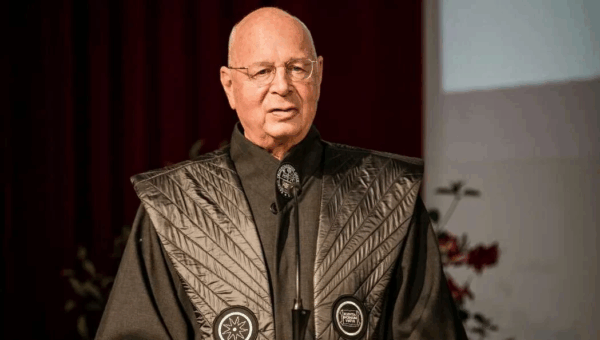

1 Swiss franc (CHF) ≈ 1.14 US dollar (USD). He was the most influential man in the world. A German engineering professor who became the grand orchestrator of global capitalism. Every winter, in the plush heights of Davos, Klaus Schwab brought together heads of state, CAC 40 executives, Silicon Valley billionaires, Hollywood stars, and representatives of NGOs. He didn’t just convene the world, he organized it. For over 50 years, he was the face and architect of the World Economic Forum, the man through whom great ideas of international cooperation passed… but also the most vehement criticisms.

At 88, the announcement of his abrupt resignation on April 21, 2025, was seismic. A simple statement: “As I begin my 88th year, I have decided to step down as president and board member, with immediate effect.” A hasty departure, without ceremony or speech, for the man who had always presented himself as the guardian of the temple of global progress.

Behind this discreet exit, a darker context. According to the Wall Street Journal, the Forum’s board of directors had decided to open an investigation into ethical and financial misconduct involving Klaus Schwab and his wife. Suspicions serious enough to break the trust that bound him to the heart of his own institution. He would have given up his 5 million Swiss franc pension “as a gesture of good faith,” but it was too late: the bond was broken. The board, made up of prominent political and economic figures, replaced him with Peter Brabeck-Letmathe, former CEO of Nestlé, pending a successor.

The World Economic Forum, founded in 1971, was his creation. Davos, his stage. Over the decades, Schwab had built an unparalleled global network, expanded his circle beyond Europe, attracting tech giants, emerging markets from the South, Wall Street bankers, and Gulf kings. Every year, the hotels in the small Grisons resort were fully booked, helicopters landed one after the other, and cameras from around the world captured the elite’s ballet. Davos alone brought in 450 million francs to the local economy. But beyond the spectacle, Schwab believed in his mission: “to improve the state of the world.”

This dream, often conveyed in technocratic language – supply chains, sustainable governance, multi-stakeholder partnerships – collided with a harsher reality. That of a world increasingly skeptical of globalized elites. Of a Forum increasingly criticized for its opacity, its insularity, and its ability to influence public policies without democratic legitimacy. To the point where the “Davos man” became a hated figure, a symbol of the disconnect of the powerful. Accusations of collusion, hidden agendas, and even conspiracy flourished. Schwab himself was caricatured as the grand orchestrator of a “new world order” imagined by conspiracy circles.

In recent years, he had teamed up with Richard Attias, a seasoned communicator and mastermind of multiple international forums, including the Future Investment Initiative in Saudi Arabia. An alliance between two summit-makers, sometimes seen as Schwab’s attempt to maintain his influence in the face of the emergence of new global power centers. But again, the chemistry was not enough to stem the end of the cycle.

Klaus Schwab exits the stage in a mix of embarrassed silence and discreet relief. He dreamed of a grandiose passing of the torch, but leaves his position through the back door, under the shadows of an investigation. The world he shaped survives him, but without him. His reign ends as all great epics too long end: in dissonance.

History will remember that trees, even the tallest ones, never touch the sky.